May 6, 2015

The Challenge

Many of today’s law enforcement and regulatory agencies face the challenge of maintaining capacity and capability within an environment of reducing resources and fiscal changes. The natural and logical reaction to diminished resources is to find a way to ‘do more with less’. This search often finds that to do more with less requires an increase in the efficiency and effectiveness of operational activity (investigations) but at same time maintaining the quality of investigation outcomes.

For many agencies, reacting to treat operational efficiency and effectiveness sometimes turns out to be a timely and often misguided departure from ‘business as usual’ and at times yields limited results. This is because with the issue of improving efficiency, quality and effectiveness of investigations many agencies make the assumption that investment in a new “Case Management System (CMS)” will be the solution.

Convinced by the promise of modern technology and the array of task management, data capture, link charting, reporting, time tracking and accountability features on offer, agencies wedge recently acquired new CMS into the operational environment. However, after implementing these new systems (often with resistance from the actual end users) agencies find that their shiny new CMS, has not yielded the promised increased productivity. Although accountability, tracking and reporting of cases has been significantly increased through the CMS, the efficiency and effectiveness of investigations has remained unchanged or in some cases actually deteriorated.

The question is why?

The diagnosis (or perhaps excuse) of this failure will vary from agency to agency and will range from a mismatch of CMS to agency needs, resistance to cultural change, implementation difficulties and a variety of other explanations. But perhaps the true reason, is that the CMS was in fact doing the job it was designed to do, namely managing the case (case management) when to achieve increased productivity, what it should have been doing was managing the investigation (investigation management).

Consider these issues which are often found to be the cause of poor investigations.

- Lack of experience of investigator

- Little or no strategic direction

- Organizational or individual cultural issues (work ethic )

- Complexity of investigations

- Mismanagement or lack of evidence

- Failure or Lack of leadership or suitable mentoring

- Misuse or inefficient use of resources

A CMS is unlikely to be able to deal with any of these issues. In fact the introduction of a CMS may actually reduce efficiency even further as investigators now have to commit a great deal of time entering data into the CMS so that the case reporting features are maintained. Investigators frustrated with complex or time consuming data entry requirements will often start to take short cuts on evidence or information management to avoid having to actually use various components of the CMS. These shortcuts or resistance can often lead to further quality control issues.

Case Management Systems (CMS) exist in one form or another with agencies. Whether it’s a simple database designed in-house or an elaborate system purchased from an external provider. Historically the primary purpose of case management systems is to record complaints , track investigation progress, report on outcomes. Some have evolved to allow upload of scanned documents and folders, relational link charting, time tracking and a myriad of other case reporting and accountability features. But do these features have anything to do with investigation management?

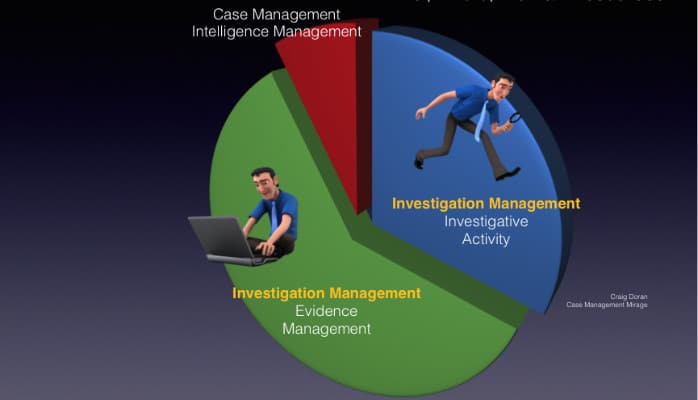

Case Management v Investigation Management

Some of the more recent discourse around distinguishing ‘case management‘ characteristics from actual ‘investigation management‘ has been framed by contrasting the ‘structured’ and ‘unstructured’ work undertaken during an investigation. While the CMS tools have delivered improved cycle times for many simple ‘structured’ parts of an investigation (e.g. recording the complaint details,capturing statistics, data analytics, reporting outcomes ), improving the cycle times of the unstructured parts of investigations such as the investigative and evidence gathering (and management) activities where costly skilled human resources are focussed – has remained often elusive.

Neil Dutton, one of Europe’s most experienced and high profile IT industry analyst expands on this issue through defining two types of work processes as ‘Transactional Work‘ v ‘Exploratory Work’. Transactional work is work in which the inputs are well-understood, the outputs are well-understood, and there’s a strong correlation between carrying out a very clear, particular set of actions and consistent transformation of those inputs into those outputs. Transactional work in the context of investigations are areas of complaint recording , task tracking, link analysis, exhibit management, business reporting and other structured activities (as often found in many CMS).

Exploratory work is very different in the way that it feels. Exploratory work is often what lurks underneath verbs like “investigate”, “diagnose”, “analyses”, “co-ordinate”, “solve”, “determine”, “arbitrate” and so on. The inputs to exploratory work may be broadly categorisable, but are probably not completely predictable. The outputs are likely to be well-understood in terms of high-level goals (see the verbs above), but probably but not in terms of tight specifications. And most importantly, the set and sequence of actions needing to be performed, and the people or roles needing to perform them, are very unlikely to be known ahead of time.

There may be some high-level waypoints or milestones that are common to a particular type of exploratory work (verify complaint, identify offender, prove the breach, secure prosecution) but they provide a very loose, rather than tight, structure. In exploratory work, as the label suggests, the overall experience for both the investigators and other stakeholders is that of a set of possibilities being explored rather than a recipe being followed.

Exploratory work is the natural and fluid work form in key parts of an investigation that touch its participants. Many CMS have tried to engineer out the variances, eradicate the exceptions and force-fit natural interactions into transactional boxes. In the age of increasing public expectations and as we witness a shift towards truly Digital Enterprises, we can’t afford to ignore the potential upside of supporting exploratory work with specialised tools that make it more effective, more efficient, less error-prone and more improvable without reducing its nature.

In summary, agencies must ensure they truly understand the characteristics of the harms, risks or issues they are trying to solve and whether they are based within transactional work or exploratory work. Failing to understanding these characteristics may lead to the implementation of new processes which improve the transactional work and reporting component of investigations but fail to have any impact on the exploratory work where the true nature of the issues exist. Agency decision makers should have a clear understanding of the difference between investigation management tools and case management tools if there is a true desire to increase the productivity and quality of investigations.

In our next article, Elementising Evidence – The Lost Craft (Part 3), we will discuss how the strategy of Elementising Evidence is the foundation upon which effective investigation management systems must be built. We will look at the risks associated with poor investigations, identify the common characteristics of harm between these risk and focus on the one simple solution that will potentially increase investigation efficiency and quality to levels not yet seen.

With COMtrac as your investigation partner, you are able to increase your front line capacity while resting assured COMtrac is by your side as your partner helping strengthen results, reducing risk and improving the overall quality of your investigations.