Back

The characteristics of harm and their role in shaping investigation management and technology

Craig Doran

Oct 31, 2025

10

Min Read

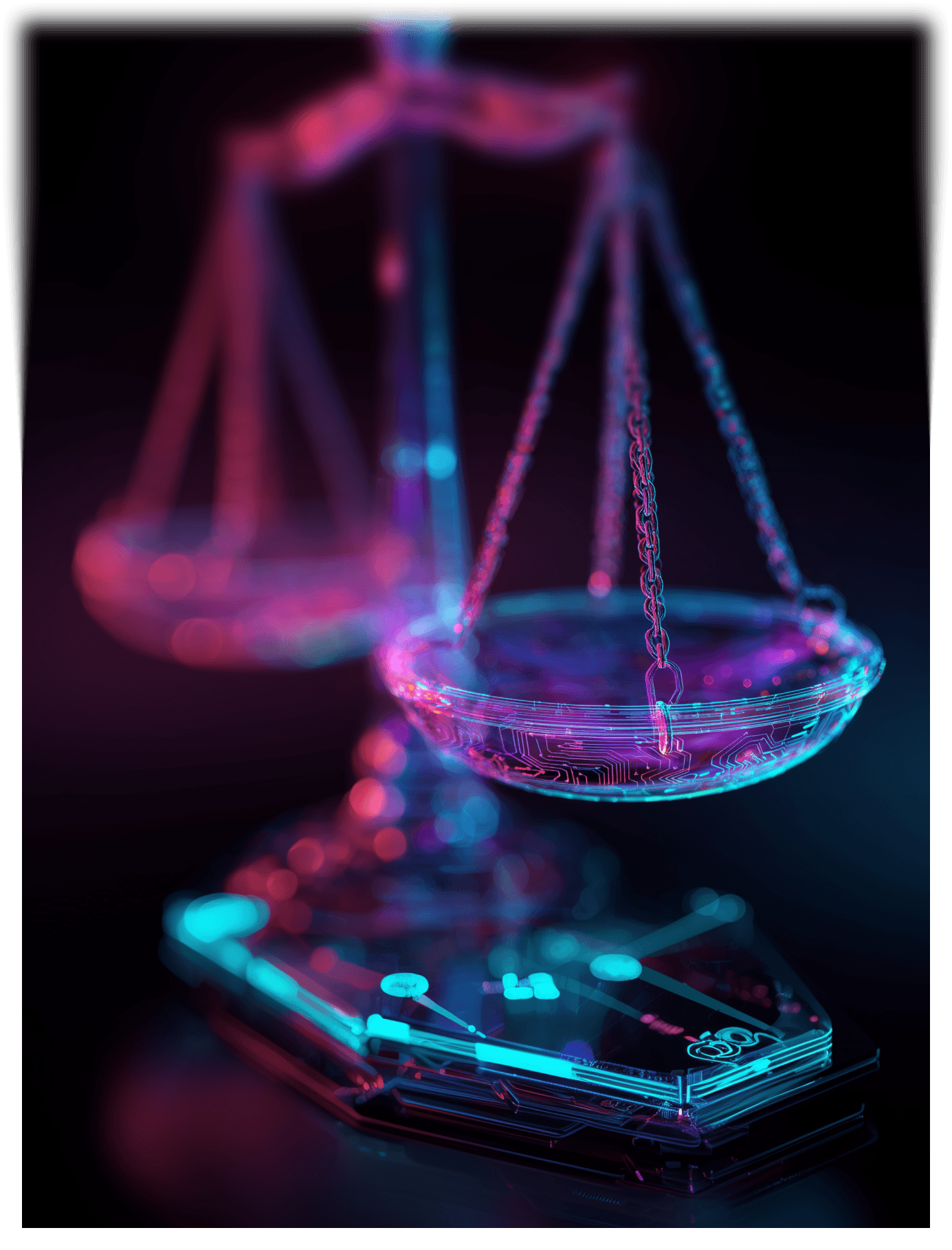

Investigations are rarely just a series of tasks. They are complex environments where exploratory work meets real-world consequences. Traditional management approaches often focus on processes, compliance, or completing cases, but this can miss the real measure of success: the reduction of actual harms.

Investigation Management is the craft that ensures investigative work is efficient, effective, and of high quality. It goes beyond simply managing tasks or closing cases. It is about enabling investigators to uncover risks, address wrongdoing, and achieve meaningful outcomes.

Yet achieving this requires a deeper understanding of the characteristics of harm, as described by Professor Malcolm K. Sparrow of Harvard’s Kennedy School. Sparrow’s research reframes investigation and regulatory work. Rather than measuring activity or procedural compliance, organisations should focus on the harms themselves, including the patterns, severity, persistence, and systemic nature of the problems they aim to control.

By understanding the visibility, scale, adversarial nature, and systemic causes of harm, investigators can prioritise work, allocate resources effectively, and design methodologies that improve outcomes. These insights not only inform how investigations are conducted but should also guide the design of effective technology, such as Comtrac, that supports investigative tradecraft rather than constrains it. If technology does not do this, then is it really aiding investigations or simply serving as an administrative tool?

What is investigation management?

The term investigation typically refers to an environment where exploratory work is undertaken. Management, by its common interpretation, refers to the efficiency, effectiveness, and quality of an operational or business activity.

From this, we can conclude that Investigation Management refers to the craft that produces the efficiency, effectiveness, and quality of exploratory work.

Increasing investigation efficiency and effectiveness

An effective criminal investigation may be where all elements of the offence(s) are proven or negated, and a reasonable or relative penalty has been achieved. An effective incident investigation is where all causes and root causes of incidents are identified and suitable, economical and justifiable preventative action, and where appropriate disciplinary action has been implemented.

Administrative investigations are effective where the alleged misconduct has been proven or negated and justifiable disciplinary action has been taken. Other forms of effectiveness may be where the impact of the investigative outcome acts as a deterrent to others or prevents other undesirable incidents from reoccurring.

When investigations fail to achieve these outcomes — when offences remain unproven, root causes unidentified, or misconduct unaddressed — effectiveness is compromised. In most cases, these failings stem not from external constraints, but from the manner, quantity, and quality of evidence gathered and the underlying investigation management methodology.

Improving the quality of investigations

The quality of an investigation is largely determined by the quality of the evidence gathered and recorded. This quality is defined by several key factors:

The lawfulness of methods used to access and seize evidence.

The integrity and continuity of evidence from seizure to presentation.

The design, delivery, and interpretability of evidence-based briefs and reports.

The relevance and value of the evidence to the investigation objectives.

The methodology of evidence identification, assessment and handling will have a direct impact on the quality of the investigation at its conclusion.

Hence, any attempt to improve investigative quality must also improve the component of the investigation management methodology that governs evidence management.

Investigation management methodology

If the common thread linking efficiency, effectiveness, and quality is the investigation management methodology, then that is where innovation and improvement efforts must be focused.

Here, it is vital to distinguish between transactional work and exploratory work.

Transactional work relates to organisational processes — the routine administrative steps often governed by Case Management Systems (CMS).

Exploratory work, on the other hand, is the craft of problem-solving and operational investigation.

While CMS platforms are built to manage processes, they rarely enhance the problem-solving dimension of investigative work — the part that deals directly with the harms an investigation seeks to uncover, disrupt, or prevent.

To truly have an impact on exploratory work undertaken during investigations, we must improve the investigation management methodology. Once we find a better methodology, it needs to be locked into an investigation management system.

Understanding the characteristics of harm

To advance investigation management, we must first understand what Malcolm K. Sparrow, Professor of Public Management at Harvard’s Kennedy School, describes as the “character of harms.”

Sparrow’s work reframes how regulators and investigators approach risk and wrongdoing. Instead of centering on processes or compliance, Sparrow argues that organisations should focus on the harms themselves — the tangible problems, risks, and damages society seeks to control.

In his landmark work The Character of Harms: Operational Challenges in Control (Harvard, 2008) and subsequent writings, Sparrow identifies key characteristics of harms that have direct relevance for investigative practice.

Visibility - hidden vs. observable harms

Some harms are visible and attract immediate attention (e.g., a workplace accident or public complaint). Others are invisible — buried in data, unreported, or intentionally concealed (e.g., fraud, corruption, exploitation).

Effective investigation management must allow for both reactive and proactive detection. Invisible harms demand analytical tools, intelligence-led detection, and pattern recognition, not just reliance on reports.

Adversarial nature - conscious opponents

Sparrow notes that some harms are caused by conscious opponents — individuals or groups deliberately working against enforcement or hiding wrongdoing.

Investigations into such harms require adaptive, strategic, and sometimes covert approaches. Systems must support flexibility, secure collaboration rather than rigid linear workflows.

Scale and severity - catastrophic harms

Certain harms are rare but catastrophic in nature. These require early detection, escalation pathways, and cross-agency collaboration.

Investigation systems should help prioritise and scale resources based on risk and impact, ensuring that severe harms are not managed with the same processes as routine cases.

Embedded or systemic harms (equilibrium harms)

Some harms are deeply embedded within organisational or societal systems and sustained by incentives, culture, or structural gaps.

Investigating such harms requires more than evidence gathering; it requires systems thinking. The investigation methodology must empower investigators to identify root causes, policy weaknesses, and systemic patterns, not just the immediate breach.

Performance-driven risks

In some contexts, harms arise because of performance pressures or incentive structures (for example, meeting quotas or KPIs that unintentionally encourage shortcuts or misconduct).

A modern investigation management approach must therefore examine how the environment contributes to harm, not merely who caused it.

Designing an investigation management system

An effective Investigation Management System that results in. Quality outputs like briefs of evidence should therefore be grounded in an understanding of the characteristics of harm within investigative work. A well-designed system must:

Address the common characteristics of harm that underpin poor or inconsistent investigations — supporting investigators in identifying, understanding, and responding appropriately to each harm type.

Be intuitive and investigator-focused, promoting adoption and consistency by aligning with natural investigative thought processes rather than rigid administrative steps.

Provide a consistent and centralised methodology, reducing siloed practices and ensuring that lessons learned from one harm or incident inform the next.

Critically, the IMS should not attempt to micromanage every possible risk or scenario. Instead, it should enable investigators to analyse undesirable outcomes, focus on areas where harms concentrate, understand their characteristics, and implement targeted, effective solutions.

By embedding Malcolm Sparrow’s harm-based framework within investigation management methodology and the technology that supports it, organisations can move beyond process compliance to achieve what truly matters - reducing harm, improving quality, and enhancing public value.

The Comtrac team will be at the Risk-Based Regulation Conference in Canberra on November 19–20, 2025, alongside renowned regulatory expert Malcolm Sparrow. Hear directly from Malcolm as he explores how regulators can move beyond traditional, process-driven approaches toward strategies that focus on identifying and mitigating real harms. |

|---|